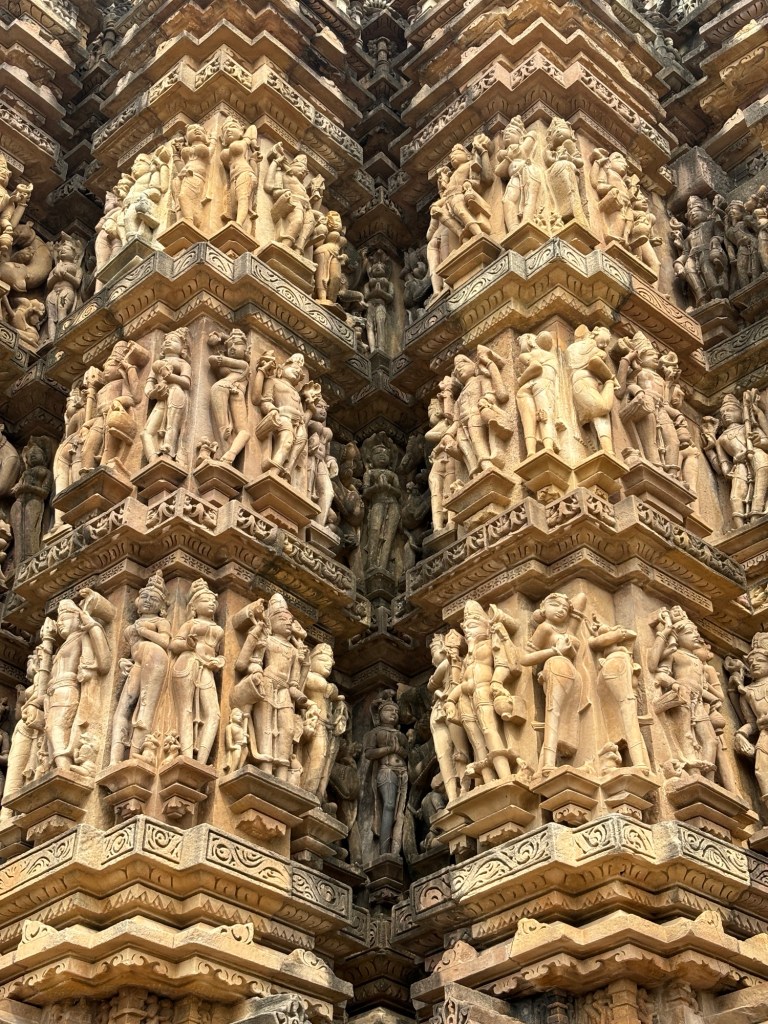

The Temples at Khajuraho are well known in the West, if infrequently visited, since they lie far off the typical travel routes. This likely helped to save them; they lay untouched, covered by jungle for 700 years before their rediscovery by the British in 1838.

The reason for their renown—especially with the rise of the internet and “click tourism” has much to do with the frankness of the sculpted bodies and the antics human bodies enjoy exploring. Although only an estimated 7-8 % of the sculptures at Khajuraho deal with erotic themes, their expression is robust and refreshingly full-throated.

After spending a month studying a geographically wide range of temples constructed in roughly the same time period, one comes to recognize the rote quality of much of the carving. This is a problem encountered in the West as well, and how a standout carving such as the “Smiling Angel” on the West (?) portal at Reims Cathedral can cause such a sculptural stir. In both the East and the West, most of this work was performed by what were known as “banker carvers,” not sculptors as we would use the term today. These were journeyman stone masons, carvers, competent with the tools, but not inventing shapes or channeling heartfelt meaning through their hands to create “energized symbols.“ That being said, it becomes clear when a gifted carver tackles a particular theme or some unrecognized talent was given an opportunity. There are moments that dazzle and break past the formulaic.

This supposition was validated by my reading of Anupma Chandwani, an Indian journalist and author who identifies an art-treatise called the Shilpa Shastras which laid down the rules for temple building. This work defined the temple’s essential parts, the auspicious and inauspicious motifs, and even the acceptable locations for sculpture.

The temple’s relation to the human body is made clear by its naming tautology. The “jingha,”literally thighs, form the walls of the temple. The “garhagriha,” literally, womb-chamber is the sanctum sanctorum containing the main idol, where the most sacred space is to be found. Makes sense to me.

According to Diana Eck and her book, India: a Sacred Landscape, the celebration of fertility in India goes back at least 3000 years. Cosmic creation through sexual union finds seeds in the Rig Veda composed in 1000 BCE. Sculptural depictions of sexual acts found in central and eastern India as far back as 200 BCE. and are found everywhere. I’ll start with some lovely examples carved in Teak at the Nepali Temple in Varanasi.

Before delving into the sculptures themselves, it might be useful to frame it within the explicit goals of Hinduism, of which there are four tenets or pillars:

◦ Dharma- religious obligations

◦ Artha- acquisition of wealth

◦ Kama- love and pursuit of pleasure

◦ Moksha- salvation

According to Upanishads the ultimate goal of man is Moksha (salvation) where the human soul unites with the Devine soul. The sexual union is the place where all sense of duality is lost and therefore symbolic of Moksha.

Rereading these ancient texts now in my sixties, I find it tremendously reaffirming. I’ve always maintained that it’s through transcendent sex, that I gain access to God; and not just God, but the creative function itself. Not everyone understands what I’m saying when I’ve expressed myself this way, and clearly, sex doesn’t ring all the bells for everyone. But for those who may have glimpsed this altered state through the sexual union at some time in your life, it will make sense that this powerful energy found its explicit expression on temple walls, pointing a path toward transcendent union with the Devine soul.

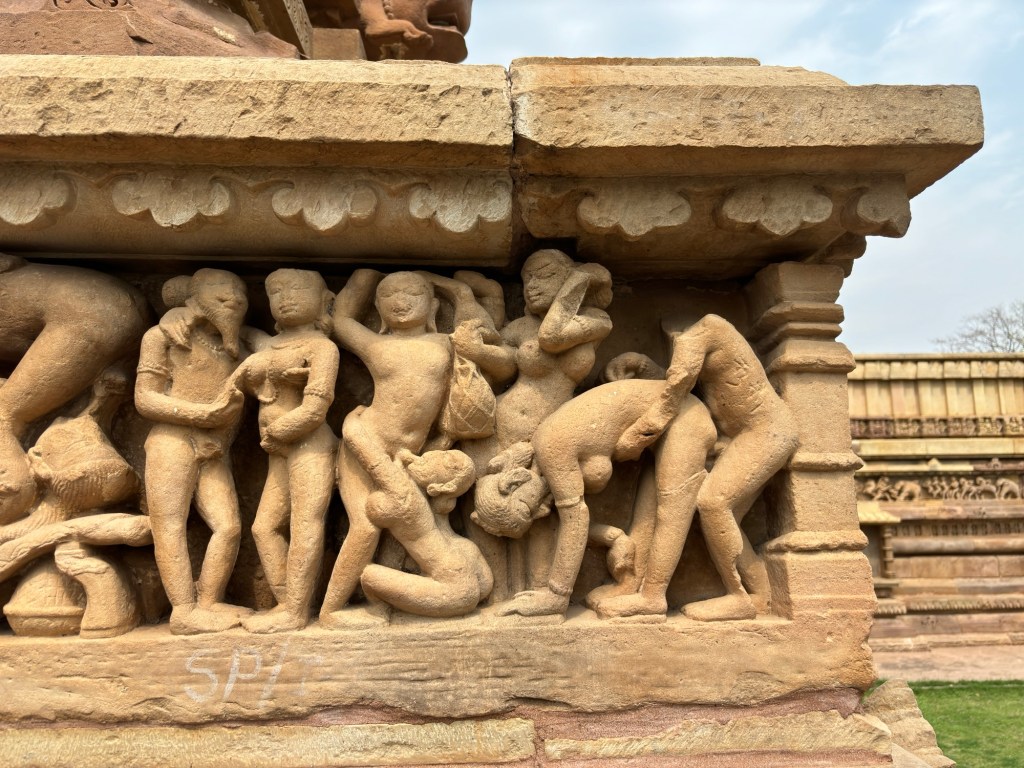

For many in the West, having grown up in a puritan orthodoxy that told young men they would grow hair on their palms for masturbating, such joy in the sexual union can be hard to square with the even the word “Temple.” So fraught are the ideals of virginity and celibacy, we can’t agree on sex education in our American schools. Even now, almost a quarter of the way through the 21st century, the highest court in our land insists on deciding what medical procedures a woman may choose for her own body. With that background, how comfortable are we in viewing scenes most of us would publicly disavow—although who knows what happens behind closed doors in America, clearly more than we have historically acknowledged. Anal sex, oral sex, group sex, sex with helpers, self- pleasuring, even bestiality, these carvings spare no options with the exception of explicit homosexuality, and that’s likely there as well, I’ve just not yet found it. How refreshing.

Although we may quibble on where the line falls between the erotic and the transgressive, most today would put beastiality squarely outside the lines. Yet, remember the Masters and Johnson report, Human Sexual Response, released in 1966 that revealed that some 20% (or was it 30%?) of American men said their first sexual experience was with farm animals? How quickly we forget.

The location of the bestiality panels is important. It’s on a low band at the temple plinth, filled with other scenes from the countryside: hunting, making war, group dancing, and music. Bestiality is not high on the temple spire, reaching for the heavens. The location does not suggest it was offering access to the transcendent function.

For those still at a loss how to think about all this, it may help to remember that Tantrism arose beteeen the 8-14 centuries as a reactionary offshoot to the austere beliefs of Buddhism and Jainism. Tantrism propounded a generous enjoyment of the senses, a personification of the Divine Energy pervading the universe.

Leave a reply to stephensmith095 Cancel reply