At Manikarnika, the main burning Ghat in Varanasi, there is a large pile of coals used to ignite the pyres that has burned continuously for 2500 years. I tried to imagine a tradition anywhere else in the world where such consistency might be possible. I could not.

I fed and kept a bread levin for twelve years until my wife made a pancake out of it and ate it. Accidents happen. But 2500 years? Wars, invasions, plagues, and pestilence, and the fire never went out? It tells us something about death and its relentless quality, that through it all, that flame was still needed and nurtured, in performance of this endless duty.

The body to be cremated, wrapped in white linen and draped in orange or gold cloth, arrives tied to a bamboo stretcher carried by four family members. They first wade into the Ganges, the holy Mother, dunking their departed for a final purification, the body then placed on the large and thoughtfully organized pile of logs. A single large coal is retrieved by the appointed family member from the origin fire; the oldest son if cremating the mother, the youngest son for the father. Freshly tonsured and wrapped in white linen, the designated family lead carries the coal in a green, split-bamboo spoon to the waiting pyre.

The stacked wood is typically one of the 17 variations of mango that grow in India and the fire burns hot and long. Sandalwood is ideal, but now considered far too expensive. Still, sandalwood shavings can be added, as a host of other herbs sold by nearby hawkers. The gold or orange drape removed, a large ladle of ghee is poured over the body prior to ignition. The smoke rises hot and fast as the body burns. It turns dark and heavy as the flesh burns away. The large pile of wood will take 24 hours before the bones and the rest are finally reduced to dust. For men, the chest cavity is the last to go, for women, the hips.

By making a donation to the hospice behind the burning site, I was given full access to the process and tour of the facility. I was even allowed to take photos. I took very few. It seemed a private moment for those performing the ritual. Fortunately, the cremation grounds do not smell like burning hair or flesh, or any of my worst imaginings. But the place is as filthy and fouled as anything I’ve ever seen. Matt commented on our tour that “When India goes dark, it goes REALLY dark.” Trash was everywhere and thickest at the edge of the river where the final purification is performed. There were even exhausted workers from the Chandal caste, sleeping in the areas where the ashes had cooled as cows and dogs nosed through the remains. “Why are the animals here?” I demanded incredulously.

“They need the salt, left from the bones.” I was told matter of factly.

(I have a video to load here once I find bandwidth. If you’re reading it now, check back to see if I was successful in a day or two)

The other funerary ghat—Harischandra—is much less used. “Only murders, accidents, and suicides.” I was told. The guide also rattled off a long list of those who can’t be burned. Stunned by it all, I only caught the last of his list. “Pregnant women don’t burn well so they are dumped in the Gagnes directly. Same with the Sacred Cow.” Ouch.

The cost is not insignificant for a family to cremate in this traditional method. The mango wood is all transported some distance and must be purchased for 950 Rs. per kilo. That works out to about $650 per pyre. But remember that the average annual income has only recently raised to $2500 a year. Many live on far less. “Electric cremation” has now become the norm for the Hindu population. Although this site alone burns 150-250 bodies a day, that only scratches the surface of demand. “Only Muslims and some Christians continue to be buried,” The guide explained.

I asked about the Sadhus covering their bodies in ash and offering to smear it on my forehead (for a small donation) at every turn in the city. “It’s to remind us to be humble. In the end, all of us will be reduced to ash.”

I was also surprised by how the caste system continues, even in the launch to the afterlife. It turns out the ghat has many tiers. Even in death, your status matters in India. The closer your pyre to the water, the lower the caste. It did amuse me to find a special area railed off higher up for the burning of “special” men: politicians, policemen, priests, and artists. Ha! That’s not a grouping I have encountered before.

The Goddess Kali is associated with cremation grounds (as well as Time, Doomsday, and Death) and often portrayed visually as wearing a garland of human heads. Depicted with four—sometimes ten— arms, she also carries a sword, representing Devine Knowledge, and a severed head, symbol of the Human Ego that must be slain to achieve “moksha” or salvation. Kali’s skin is always black—except when it’s blue—reportedly suggesting she is beyond time and material things. I have always instinctively identified with her and in the last five years have encountered her several times in my dreams. Jungian analysis is helpful in such moments.

I was raised by a “dark mother” and the destructive anger of Kali is something I knew too well growing up. It was the water I swam in and has taken my entire adult life to crawl onto shore, stand upright, and learn to walk as a man. Evolution is slow and hard work, but it can be accomplished. That backstory may have something to do with my reason for showing up at the burning grounds, spending time in “full reception mode,” and thinking about next steps to be made with what remains of my life.

Although the sight of a human head burning, or leg and foot akimbo in the flames, was completely new to me, I felt no panic and only mild revulsion. It seemed clear the life spirit had long shed these human forms and this disposal performed a natural and sanitary way to deal with the remains. I accept that others may come to different conclusions.

There was one incongruous moment I want to share. To reach the sacred “origin fire” one climbs a series of filthy steps where the blown ash and smoke from the funeral pyres has settled for a millennia. It’s not for the feint of heart. Sitting on a dirty white chair facing this fire was one of the first Western women I’d seen on the trip. In full makeup and dressed causally in pristine white, she sat motionless, eyes closed in what I assume was meditation. Likely about forty years old, she was exceptionally beautiful and seemed to glow in this discordant setting. Funerary workers and family members came and went to retrieve their ignition coals. She never moved, never opened her eyes, and no one disturbed her.

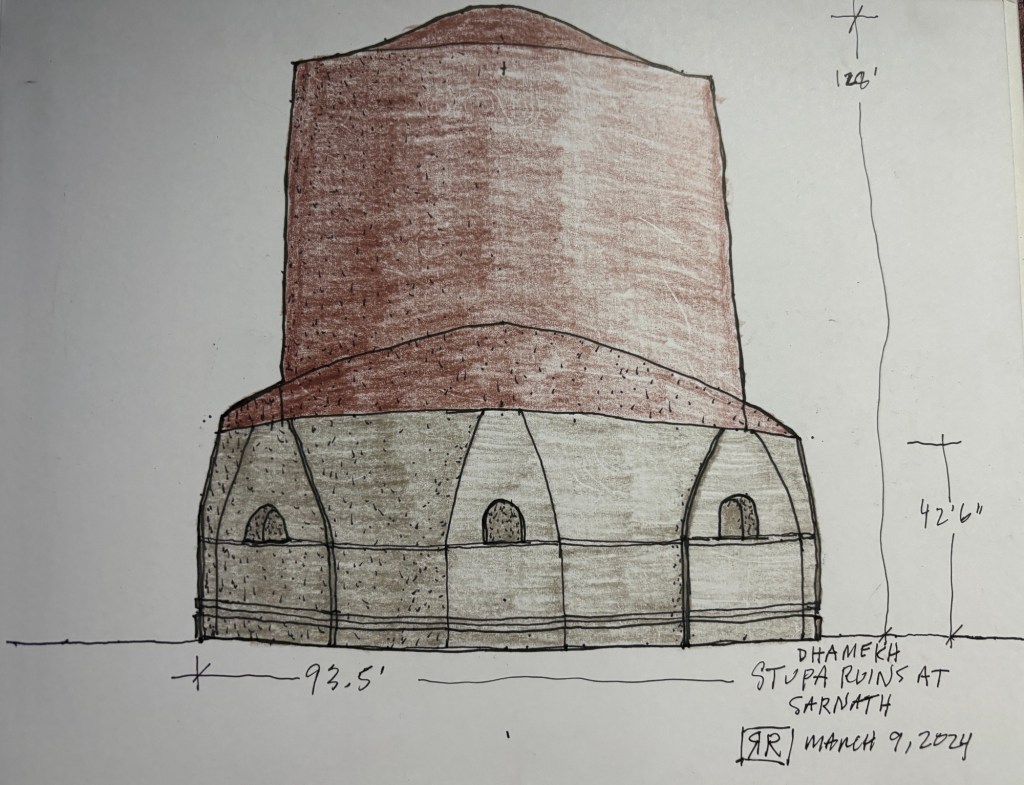

Later that day in the important Buddhist center Sarnath—where the Buddha gave his first sermon after attaining enlightenment—I encountered a second group of about ten Western women sitting in a circle under the shade of a large tree, also meditating. They were younger, late twenties perhaps, and similarly isolated. There was no way to say hello, exchange notes or trade local intel. They were locked inside and the rest of us were locked out.

This might not be so different from the high-end tour groups of retirees that moved through Varanasi and Sarnath; masked-up, linked by hands so as not to get separated, and marching ahead, determined to follow the program of their proscribed tour, their feet never really touching the ground. They stayed remote—four-star hotels outside the city—ate western food in the hotel cafeteria and moved in a phalanx. There was no way to reach them, say hello, or inquire of their experience. Most carried huge daypacks and cameras with long lenses but linking arms to stay together, never had time to look up, let alone take a photo. I found it sad, but also isolating. Not once on the trip did I met a fellow foreign visitor who might be interested in how Matt and I traveled or what we had found. We were burning with questions on where else travelers had unlocked ancient secrets, but found no one to ask.

In speaking with hoteliers during our stay we learned the Western travelers “vanished” after Covid and have never really returned. The back-packing crowd is especially missed since they actually tended to engage with India and the locals enjoy this exchange. They were shocked to learn I was American explaining they had met almost none since 2019.

Among my American friends and colleagues before I departed, I heard versions of the following: “India? That’s just not a place I need to see.”

My heart breaks at this response. Of course, travel here is tricky, uncomfortable, and in-your-face challenging. But it reminds me of the real work involved in having and raising children. If we really knew how hard it was, would any of us really do it? And wouldn’t our lives have been a shadow of their potential without that seminal experience?

Perhaps the way to approach travel in India is the way we might prepare for any big experience. Train for it. Build resilience. Find ways to push through some discomfort and unpleasantness as part of the grand bargain to live life more richly. India’s accomplishments and potential stagger the mind. The cultural richness is beyond compare. To paraphrase the British historian, Patrick O’Brien, I grow weary of the “arrogance of Rome” and the “scientific and technological triumphalism of the West.” In the mid-twelfth century CE while Paris and London were no larger than tiny cities of 75k and 50k citizens respectively, the Indian kingdom of Hampi had a standing army of over 1 million! Imagine the infrastructure required to house a feed a million fighting men. These questions were somehow left out of my poor Western education. And face it, as we age, our circles winding more tightly with what we know and are comfortable with, acquiring these insights becomes harder. But does that mean we should stop trying? Have any of us really seen enough, understood enough of this complex world?

We can point to mobility in aging as one of the turning points where we are forced to limit ourselves in significant ways. But it seems we might need a term for the feeling that seems to come a decade or two before; a feeling I’m noticing with my peers. It seems to say “we’ve seen enough, and are willing to sit out the last several rounds as we enjoy what we already know.” There is no harm in this. But if someone I trusted told me there was an amazing neighbor just round the globe with one of the richest human traditions on the planet, I might be inspired to go knock on the door and introduce myself.

Food for thought, I hope.

Leave a reply to Kenton S Lissack Cancel reply