It might be skimming the edge of the hyperbolic to say that one of architecture’s great struggles has been to dome—read circle—the square space it rests on. Istanbul’s Hagia Sophia and Brunelleschi’s dome for the cathedral in Florence are not just milestones in the development of the form, they stand as breakthrough achievements that changed the course of architecture itself.

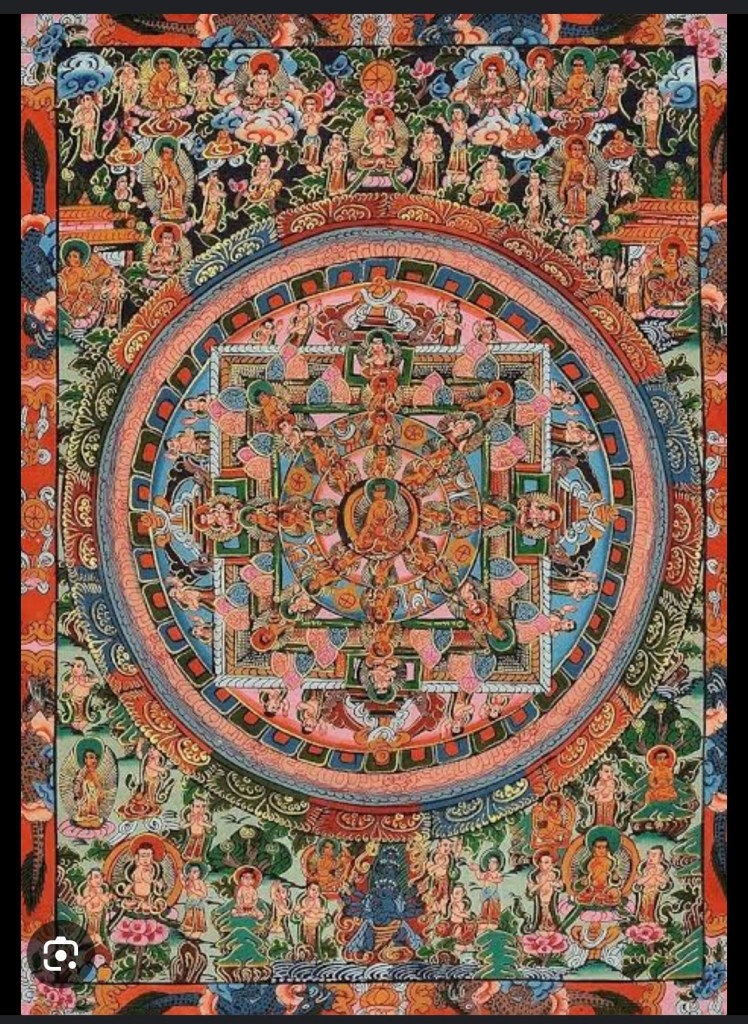

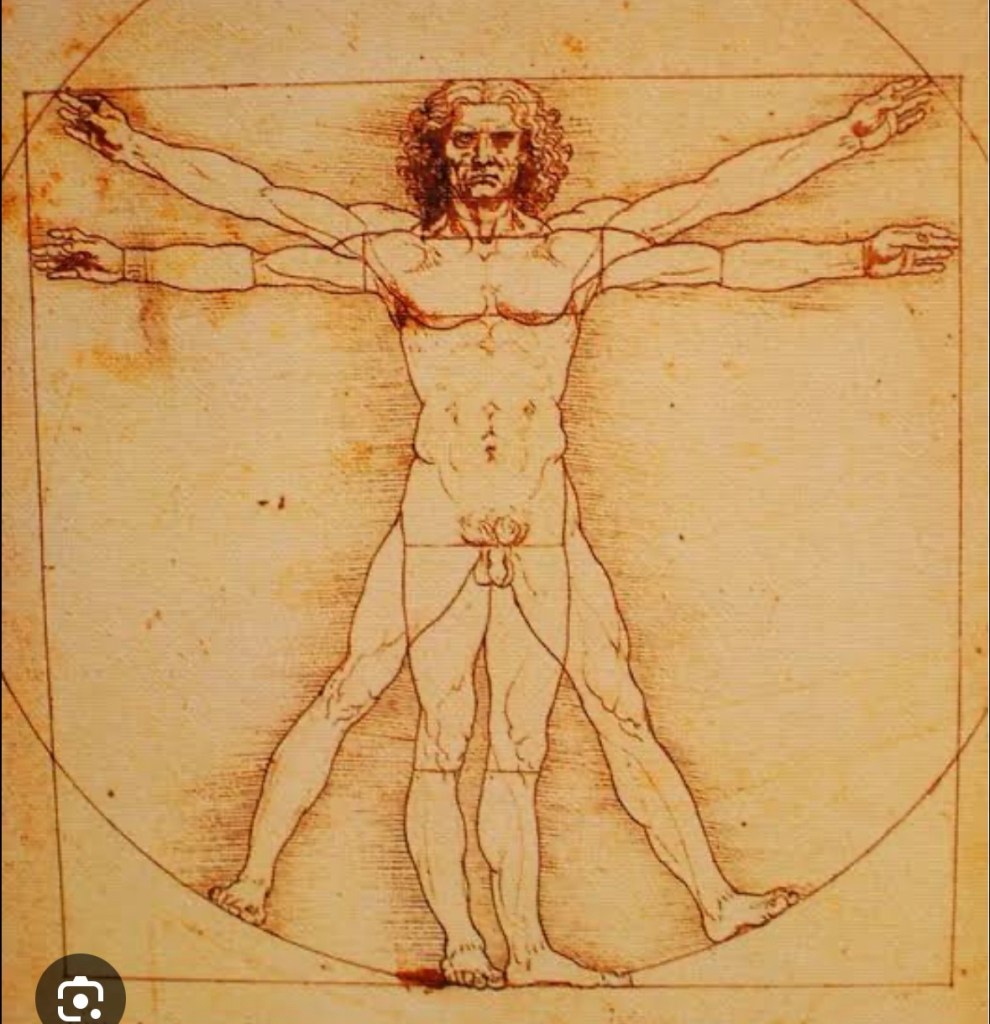

Of course, this effort to resolve circle within the square also offers a profound metaphor for the transformation of the human soul. Many Buddhist mandalas sit within the square frame of ego consciousness, and even Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man diagramed man’s extremities within the circle and square, hinting at the divine symmetry implicit in the human form. Within the medieval guild in Siena where I formally trained, squaring the circle was primary to the Sacred Geometries and central to the closely held secrets.

Interestingly, I dreamt this visual symbol this week and upon awaking, decided I would explore the concept in a blog posting. Not one hour later, out of the blue, Matt used exact phrase in a discussion of sculpture; how when the form finds harmony, one has, in fact, “squared the circle.” I love such synchronicities and, as I’m fond of saying, “If you think it’s all a big coincidence, then you’re not paying attention.”

At the hill fort at Kumbahlgarh, we find clear examples of several successful squaring the circle strategies. For smaller domes, an overlay of large triangular stones cantilevering from each 90 degree corner is a common solution. A second course then extends and bridges those stones on the forty-five and the void is almost closed. A third course, a single large stone, caps and closes the void. The backside of these stones (away from the void they cover) would be pitched off to shed water. Finally, several coats of render (a plaster coat used structurally for waterproofing) would be applied. Sometimes this is wrapped with exterior courses of wrought stone. This method works for very small scale domes, say 6-7’ (or less) in diameter and often forms the hallway roofing we have seen repeatedly in early Jain Temples. In the best examples, these simple dome assemblies are elaborately carved on the underside, some with breathtaking complexity. Unfortunately, Jain temples that are actively in use (like Dewali at Mt. Abu), do not allow photography; images are typically available online.

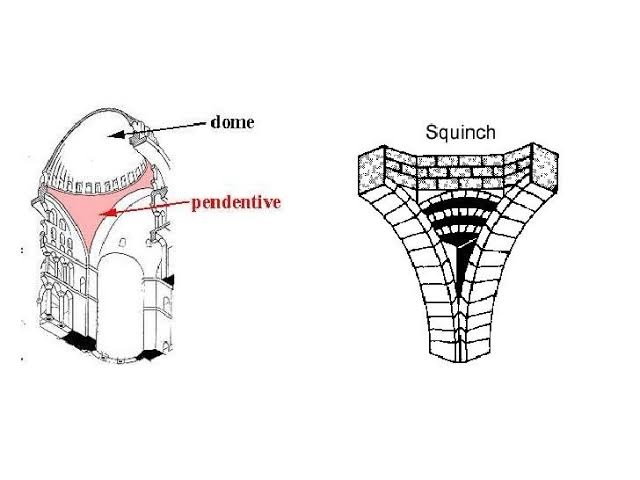

For the larger openings, the squaring of the circle becomes much more technical and tenuous. In most western architecture, a funny cantilevered shoulder called a “squinch,” is placed in each of the square’s corners as a way of cheating the dome’s support inward. This is done to offer purchase to the dome (circle) that must be supported over the (square) volume below.

In India, a different approach has been developed. This method uses a five-sided capital to support an extra lintel that spans the square volume’s corners. Although this works well, the forward leg of the capital that supports this lintel (the capital leg pointing toward the center of the space) does not extend orthogonally as one might expect. Rather this forward leg heads out at 60 degrees to give maximum support to the dome (circle) above. Confused? My drawing below should help.

To my eye, although this method obviously works well and has stood the test of time, the 60 degree angle looks off. It doesn’t project forward in the way one expects and therefore sits uncomfortably. Thinking back to my early guild training in Italy, This may be one of those textbook examples my teacher and master mason of the guild—Maestro Fabrini—would cite. He would often try to explain that even if something is technically perfect, “if it looks wrong, we have failed.” This concept, known as “make it sweet to the eye,” opens the path to a host of visual sleights of hand at the center of craft mastery—in both sculpture and architecture. It is what makes the Parthenon in Athens such a compelling building. As I’m sure you may remember, there are multiple sleights of hand that bend the lines of the Parthenon to make sure the result sings and remains sweet to the eye. In sculpture, it’s the elongated neck, or lengthened leg. Having it accurately reflect the form is secondary. It is far more important to feel right.

Leave a reply to Stephen Smith Cancel reply