Finally making our departure from the sick wards of Mt Abu, we felt a little tentative. Were we actually strong enough to ride? Neither of us really knew.

Unable to delay this test any further, we set off at 9:00 AM, cautious, but in high spirits. Approaching the downward grade, we spotted a familiar solo traveler waiting at the bus stop; a Greek woman in her late thirties whom we had spoken to three days earlier. She too had been ill upon arrival and recovered in Mt Abu. Now mostly better, she confessed to feeling equally tentative. We joked about all of us needing adult diapers, a welcome moment of levity. I offered that I had met a forty year old French botanist who has spent February’s for the last decade in this part of India and he confided that he too had been ill for ten days this month. “I’m a regular, know the drill, and have a strong constitution. I couldn’t believe it.” He said. I confessed to him that I too had 23 years experience in India and was left scratching my head with this unpleasant constitutional issue. Even on my last trip in 2016 with my wife and three youngest daughters—traveling deep in the Western Ghats—no one succumbed in 12 days of off-the-grid exploration.

“I met two Italians who recently arrived and they too were ill.” She added.

“Well, something’s going around!” We all agreed, almost in unison.

Luckily, on this day the Rajasthani countryside delivered our first full stretch of extraordinary riding. The impeccable grade down from the Hill Station was delicious, with big vistas and thick stone walls to protect us from the precipice. Arriving an hour later to the bottomlands, we enjoyed a second Chai before turning North on to a series of farm side-roads that meandered through endless small fields, all cultivated by hand. In the absence of tractors, you see very different textures to the growing crops. There is a comforting undulation in two meter widths to the landscape, where the hoe or shoveled bed ends, and a new crop-row begins. I was reminded of Virgil’s Georgics where he lovingly outlines the spacing between olives and vines, to allow the pollination by the bees. There were also a few fields actively being tilled with oxen, as well as many crops being cut with hand scythes and sickle. The crops included wheat and lush grasses (perhaps alfalfa?) fed to the domestic animals. We shared the road with few motorcycles and no almost no cars. Our hearing was not damaged by explosive horns. Our adrenaline was not spiked by an endless series of near misses. We were safe, mostly on route, and most importantly, feeling healthy.

Although we had planned a short day, the familiar end-of-day hotel debacle added sixteen miles bringing the total to 49. Again and again, hotels that existed on Google failed to materialize. One proved to be located inside the company town for the local cement plant. We were not allowed to enter. Exasperated, we backtracked 8 miles to the interstate we had so successfully avoided all day. In the day’s last light, we arrived grossly overtired. The rooms were rough but we were not in a position to negotiate.

Slightly larger than a prison cell and painted the same color, the “hotel’s” toughest issue was the sound of the highway fifteen meters away. Imagine sleeping in the middle of the Mt. Baker Tunnel, except every second truck is blaring a different, soul-shattering horn. Oh, and no shower, no flushing toilet, no towels—there was a sink but it wasn’t plumbed. The bed was a slab of plywood with a dirty sheet on it and a thick carpet like “blanket.” For the first time this trip, I dug out my summer sleeping bag and inflatable pad; a Godsend.

Despite all that, we ordered local takeout and it was sublime. The dahl fry was particularly memorable.

My “super-power” might just be that I can sleep anywhere, anytime, and almost for any duration. My girls have a special folder of blackmail photos of Dad, mouth wide open asleep somewhere improbable. During those decades when I was flying constantly internationally for work, I would often be asleep before the plane took off and get a solid 6-8 hours of sleep if the trip was long enough. Not fair, I know.

But this night my super-powers failed me utterly. I ranged around sleep’s bardo, in and out of consciousness. I told myself the trucks would likely stop or thin by midnight, then two AM, then four. It never happened. I must have drifted off for real at some point since I had a compensatory dream about being a passenger in an old Rolls Royce, being delivered to a fancy British club for lunch. When I emerged from the car, butlers in black tie snapped to attention. Curiously, they were all wearing yellow shirts under their impeccable black suits. What could that possibly mean?

At five AM while packing for our speedy departure, I felt janky, almost hungover; jittery too, like a drug addict getting desperate for a fix. I know many who suffer from insomnia and such a night does little to even the scales. Still, my poor night filled me with empathy.

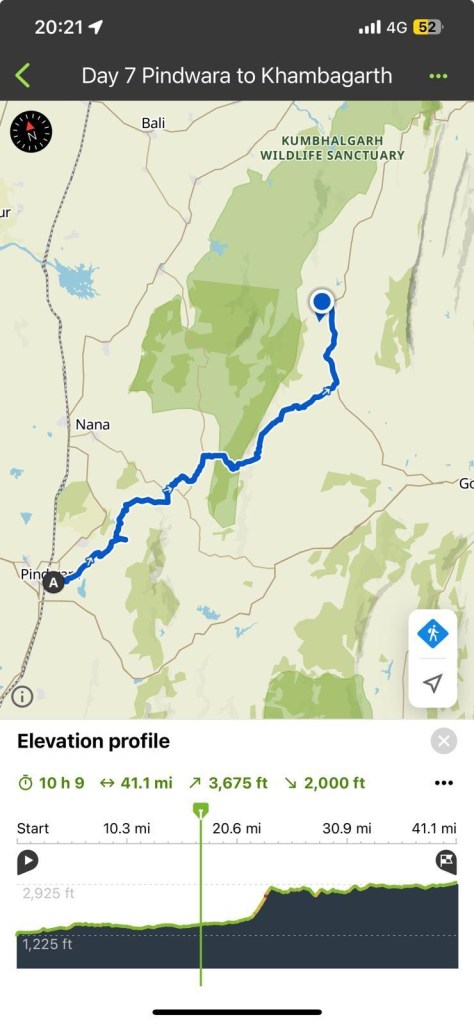

Thirty miles into our rolling ride through the foothills, we turned sharply toward the rising mountain. Although we started in the surprisingly cold pre-dawn, we were fully warmed up when the grade got serious. Although our approach that morning had included several 6-8% short sections, as the mountain begin in earnest, the grade shifted to 10-15%. Fellow cyclists will know that a grade of this pitch is essentially unrideable. This is obviously a hill (all 3400 vertical feet of it) that one will have to walk. Yet, there goes Matt, fully loaded, with 40 lbs of gear and only 72 hours out of the hospital, riding to the top. Who is this guy? Who does that? How is that even possible? How is he keeping the front wheel on the ground? I was incredulous.

Feeling not a day over seventy-five (I’m only 63), I pushed and pushed and pushed the bike for the next several hours up this impossible grade. Some sections were so steep I struggled to even do that, my touring sandals slipping on the loose roadway gravel. I was reminded of my first Alps crossing on a tandem after grad school in London. Coming out of several big grades in the German Black Forest, my girlfriend and I hit an 18% grade approaching Freiberg (near Basel). The road was so steep the two of us almost failed to push the loaded tandem. It took everything we had.

Now Matt is nine years younger and his bike has a third chain ring in front which provides slightly lower gears. Reminding myself that only a bad sculptor blames his tools, I am forced to acknowledge his performance unequivocally. It was stunning.

As difficult as the riding was, it was also ideal, and neither Matt nor I wouldn’t have changed it for anything. The route was world-class and if anyone is interested in riding Rajasthan, I hope they will consider including it in their planning.

Leave a reply to Vanessa Buxton Cancel reply