Although I have studied the ancient step-wells of Gujarat, this visit offered my first physical encounter. Matt and I visited five in total, three in Ahmedabad and two on our countryside route. Each has its specific strength and, although they vary enormously in degradation and repair, each offers unique insights into the built solution the step-wells work to solve.

The reason these step-wells occur almost only in Gujarat is directly related to the unique soil conditions. Although over-simplified, one can view the vast administrative district that is Gujarat as a giant sand bed compacted over millions of years. This ancient quartz sand is fused together—welded, as we say in geology—by constituent minerals carried through the migration of ground water (typically calcium). This eventually created the sandstone from which the step-wells are constructed. Uniquely, this sandstone was not so compacted as to make deep excavation impossible. Further, it is obvious to me that the sandstone hardened as the groundwater or “quarry sap” evaporated. This is a common characteristic of many stones including both Bath and Portland limestones (found in England) and slate, found widely in Wales and the North Eastern United States. This unique attribute allowed the stone to be excavated and carved with simple iron tools of moderate hardness, allowing fine detail without unreasonable reasonable effort.

This special geology also allowed the excavation to be made without the deep hole caving inwards and killing the builders. It is no small feet to excavate a 6-8 story deep gash in the earth. With a worldwide average topsoil depth of only 2”, even today the carving downward into the regolith remains a formidable task. Ask anyone who has built a home and decided they needed a basement. It’s never as simple as it sounds!

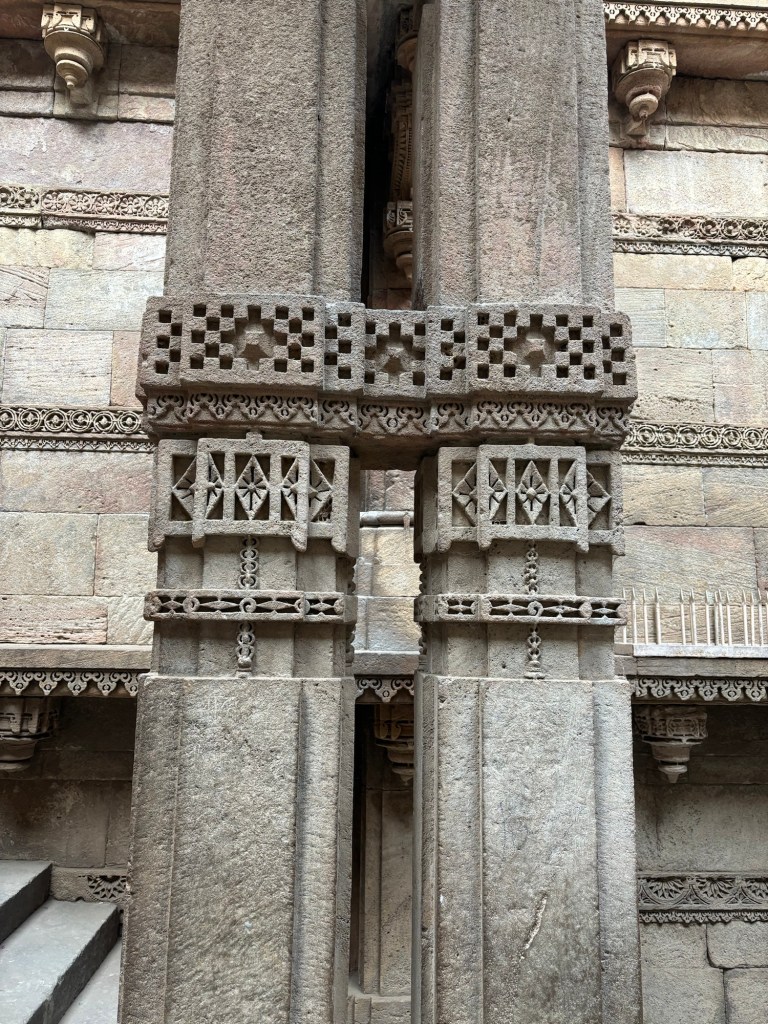

The builders quarried the blocks from the same site where they intend to build. Stock-piled nearby and protected from drying out too quickly, the stone would be shaped and carved in its “green”state. This is called “living rock” (when the block still contains the “quarry sap” or groundwater. This “fresh” state normally lasts a year before the block dries out and fully hardens. Carving stone in its green state, allows a level of detail not available to the carver using dried or “dead stone.” This topic requires a much more complicated explanation than I can manage typing on my phone from Rajasthan. However, if you want to learn more on this topic, I hope you will consider buying my book being published by Princeton Architectural Press, due out April 2025.

The first several years of excavation and building would have been focused on the structural members: the stairs blocks, wall blocks, columns, and lintels that define the larger form. Some of these—columns and lintels—may have been carved in a preliminary way prior to setting; nothing too elaborate lest the carving be damaged in transport and assembly. Once in position, these structural members would be elaborately carved in situ.

The most elaborate and figurative panels would have been carved in large blocks in nearby workshops and set fully finished. Such elaborate under-carving requires a horizontal surface and full 360 degree access to the carved composition. Once completed, it also requires extreme care in the transport and setting. All of this gives scope to the significant achievement the step-wells represent.

Step-wells are divided into two distinct sections. Today, we tour the bathing pool. That’s what’s on offer, the rest remains gated or roped off from view. Still, the bathing pool was always the primary focus with its elaborate panels of carved gods, aspirational figures, and geometric panels par excellence. This was always the public area. It is completely distinct from the other life-giving function these structures offered; clean drinking water year round.

At the far end of each step-well is a separate access to the Kingdom’s water supply, the well itself. One can imagine the massive wooden pulley, driven by livestock to lift the clean water up the many stories (depending on season and groundwater level), up and out of the deep well. I read once that only six feet (about two meters) of undisturbed soil is all that is required to clean drinking water (I’ll have to search my library at home to footnote that insight). I estimate these step-wells had at least twelve feet of soil between the bathing and drinking areas.

Also remarkable—and impossible to photograph—are the spiral staircases that descend on both sides of most of the drinking wells. These were tight, practical access portals and navigating the ones we were allowed to climb took concentration and care.

The architecture itself is “post and lintel” construction, a technique perfected by the Egyptians as early as 3300 BCE. So not much new in that regard. Still, the excavation and carvings carry the day. They’re great works of human mastery and have made an important contribution to our world’s architectural patrimony.

Leave a reply to geof73459186f61 Cancel reply